.The Gallery.

"People misunderstood my work. I am not a surrealist; I am an existentialist." ~Louise Bourgeois

This gallery is devoted to shedding some light on certain aspects of Louise Bourgeois' art work. Many of her pieces are very confrontational, and stir up many emotions in the viewers. Below are a selection of works that highlight Louise's artistic talents and were chosen based on their content and visual appeal. The interpretations of these works are based on journals, published books and of myself, the author. Although these works can be interpreted by you, the viewer, however desired.

|  |

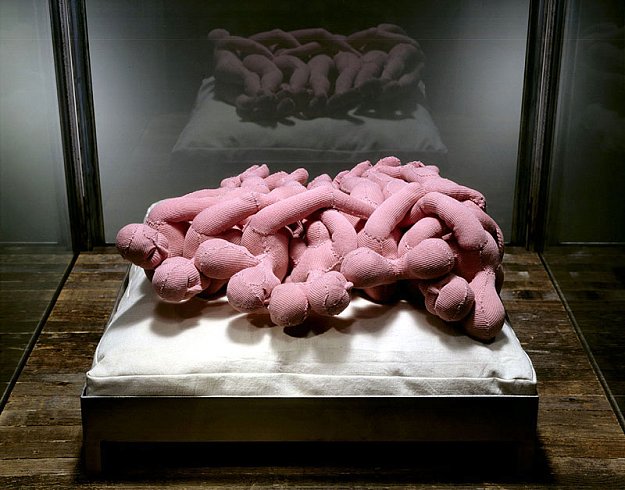

Louise Bourgeois, Seven in a bed, 2001, Fabric, Stainless Steel, Glass and Wood, 68 x 33 1/2 x 34 1/2 inches

photo taken from http://www.cheimread.com/artists/louise-bourgeois/?view=selected&subgallery=2 and http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/3668414/Louise-Bourgeois-The-shape-of-a-childs-torment.html

Seven in a Bed

Louise Bourgeois is old, but the vigour of her imagination is clearly ageless. She has said and shown that her sculpture is her body. Seven in a bed is a late piece of her manic joy - sweet, erotic, and funny. It borrows from and transforms the vocabularies of modern art. It is feminine and masculine, terrified and bold, soft and hard. It speaks in the language of space and form, and plays with both recognition and strangeness. Seven in a bed has many meanings, and was meant to evoke the hidden feelings that lurk within every human.

Seven in a bed is where childhood innocence, fairytale and nursery rhyme are reexamined in the light of adult knowledge and experience. However, while using autobiographical, personal memories as a source of inspiration, Bourgeois transcends the particular to achieve a universal art that involves the viewer in ways that is often disturbing, sometimes shocking, but never unsatisfactory.

Bourgeois has always been preoccopied with themes of childhood, sexuality, trauma and alienation. This piece displays her interest in the human body in particular - how it is constructed, dehumanised and objectifed. Bourgeois both forms and deforms the body, initiating a sense of estrangement through disturbing poses and missing limbs. Depersonalising her figures by not giving them the detail of a specific individual and by dismembering parts of the body, the focus becomes an examination of the construction and deconstruction of the body and the traditional depiction of the human figure in sculpture.

Louise used dyed fabric to cover stainless steel which is encased in a glass "room". The room may be symbolic of the secrets humans have, but these lies can be seen through as simply as we see through the glass room.

. . .

|  |

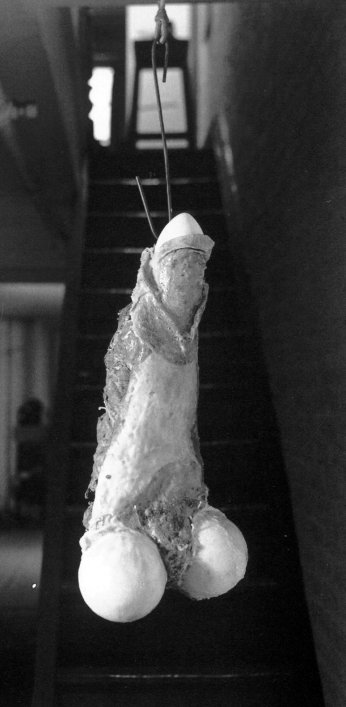

Louise Bourgeois, Fillette, 1968, latex over plaster, 59.5 x 26.5 x 19.5 cm,

Museum of Modern Art, New York City, NY (Photograph: Peter Moore)

photos taken from http://www.tate.org.uk/tateetc/issue11/lumpsbumps.htm and The Oxfard Art Journal, Vol. 22, No.2, pg 43, found at: (http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.morris.umn.edu/)

Fillette

Bourgeois' art is about trying to hold the misery up to view, and by doing so to stop herself from handing it on. More than anything else, her work is about the anxieties and responsibilities of womanhood. On Fillette, a sculpture of the male phallus, Bourgeois says

"when I wanted to represent something I loved, I obviously represented a little penis." (Taken from the article: "A Defence of Louise Bourgeois - Christie Davies and Richard Dorment are wrong about Louise Bourgeois, argues David Wootton: Louise Bourgeois at Tate Modern", by David Wootton)

Her most famous and most photographed “erotic” work is this latex sculpture, which playfully confuses genders. While it is obviously a 2ft-long phallus, it is comic and diminishing rather than commanding. Bourgeois emphasized her jokey French name for the object – a little girl – by calling it “a little Louise”. In one photograph, suspended, it resembles a toy clown in a hat and overcoat with big round boots. In a celebrated photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe, she holds it tucked casually under her arm like a baguette (this photo shown on the home page)

The Fillette is more than a humorous representation of the male ego. It symbolized Louise's trouble with the men within her family. Her brother died at a young age in war and her father was mentally abusive to her and her siblings. Louise's love for her father and desire to please him led her to create sculptures like Fillette to show her desire to be the son her father always wanted her to be.

. . .

|  |

Louise Bourgeois, Maman, 1999, Steel, 35 ft in height, Tate Modern, London (left)

photos taken from http://www.flickr.com/photos/cybertect/2069389382/ and http://scienceblogs.com/zooillogix/2007/10/giant_spider_attacks_tate_mode.php

Maman

Bourgeois was the first artist commissioned to fill the Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern in London. What she did was a sight to see. Louise created a 35 foot high steel spider that she called Maman, which is French for mother. The hall has towers surrounding the center and Bourgeois imagined that these platforms would become the stage for significant conversations and human confrontations. All of Bourgeois' sculptures incorporate a sense of vulnerability and fragility. Her works are often viewed to have a sense of sexuality to them, which she believed is a large part of both vulnerability and fragility.

Maman is a steel spider that Bourgeois has said is representative of her industrious mother, who spent her days repairing, restoring, and reweaving. Although the spider is representative of her mother, it is also representative of Louise herself, who is spinning her own web, and pulling art out of herself. Louise loved her mother, she was her best friend and Maman is a depiction of who she was and who Louise hopes to be.

Maman is one of Bourgeois better known works and has been replicated many times. The original installation was later dismantled. Many copies of the installation, cast in bronze, still exist around the world.

. . .